ROCK PAPER RADIO is a dispatch for misfits & unlikely optimists by your favorite hapa haole, beet-pickling, public radio nerd. It’s a weekly email newsletter that shares three curiosities every Thursday - something to hold on to (that’s the ‘rock’), something to read (that’s the ‘paper‘), and something to listen to (you guessed it, that’s the ‘radio’). Themes include but are not limited to: rebel violinists, immortal jellyfish, revolution. Thanks for subscribing and spreading the word.

This essay is part of #AZNxBLM, a collection of solidarity-inspired projects by ROCK PAPER RADIO and The Slants Foundation. The best way to be part of this movement is to join us on Instagram @rockpaperradio, and to keep an eye on our website here. Here’s our project’s mission:

#AZNxBLM is calling for solidarity and collaboration between members and allies of our Asian community and the Black Lives Matter movement. We are pro-community and anti-racist. We believe in the power of art and the insights of outsiders. We are cautiously but fiercely optimistic

On March 16th, 1991, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins went to Empire Liquor in South Central Los Angeles to buy a bottle of orange juice. She placed the orange juice in her backpack with the top sticking out and approached the counter with two dollars in her hand. The woman behind the counter, 51-year-old Soon Ja Du, thinking that Latasha was trying to steal the orange juice, grabbed her by her sweater. Latasha punched Du in the face. After a struggle, she left the orange juice and turned to walk away. Du retrieved a gun from behind the counter and shot her in the back of the head, killing her instantly.

Du was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. However, the judge sentenced her to no jail time—only parole, community service and a $500 fine. About a week before the police officers in the Rodney King beating were aquitted, a state appeals court upheld Du's sentence. Even though Latasha Harlins isn't a household name, her death played a significant role in sparking the 1992 LA Riots.

Steph Cha is a crime writer from Los Angeles, California. She wrote the Juniper Song trilogy, a series of mysteries featuring a young Korean American amateur detective.

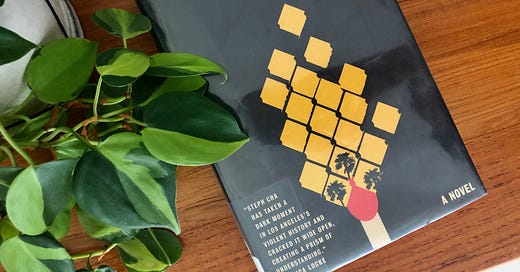

Her fourth book, Your House Will Pay, reimagines the legacy of the Latasha Harlins case and its effect on both families. Told from two points of view, it follows Grace Park, a sheltered 27-year-old Korean American woman living in the San Fernando Valley with her parents and Shawn Matthews, a 44-year-old Black man living with his family in Palmdale. Shawn’s sister, Ava Matthews, died under tragic circumstances when he was a kid. Grace’s mother, Yvonne Park, harbors a terrible secret. Grace is the dutiful daughter, while her sister Miriam has disavowed their parents altogether.

I first met Cha at a crime writing workshop at a local college in LA. She talked about her most recent book and the inspiration behind it, specifically the shame she felt as a Korean American about Latasha Harlins.

That stuck with me. When I saw ROCK PAPER RADIO’s call for pitches on Black and Asian solidarity for #AZNxBLM, I reached out to her for an interview. Even though the inspiration for this interview started with a shared sense of shame, it ended with what I'm going to call radical accountability.

Your House Will Pay doesn't provide easy answers to the question of Black and Asian solidarity. As Cha says, "There's no Kumbaya here." As Americans, we are all entangled with our collective history of oppression and injustice. In that context, Cha's realism feels profoundly hopeful. It grapples with reality and doesn't seek resolution, doesn't demand solidarity, doesn't wipe the slate clean. There is no absolution. All we can do is continuously reckon with our own power, privilege and past.

TU: When did you get the idea to split the chapters between Grace and Shawn?

CHA: I knew pretty soon after I conceptualized it that I was going to write from Shawn's point of view as well as Grace's, because I didn't think I could do justice to the story without getting deep into both families. I was afraid that if I only showed Grace's point of view—which I considered—because it's easier for me to write from the point of view of a Korean woman—I thought that there was a real danger that I would flatten the Black family and make them less interesting and therefore less easy to empathize with. I was a little worried that the only way I'd be able to write them without getting deep into the point of view was to write them as angelic and uncomplicated, and I didn't want to do that.

TU: How did you prepare to get into Shawn’s headspace?

CHA: I did a lot of research as a starting point. I talked to people about that time period. One of my best sources is a friend of mine—he's a middle-aged Black guy who grew up in LA and would have been around Shawn’s age in the early 90s—he'd gone to Latasha Harlins' high school just a few years behind her. I bought him a lot of drinks. He told me his stories about growing up, including being at the New Jack City premiere that starts the book—I heard about that event because of him.

There's always a research layer that you have to burn off later, so it doesn't feel like pure sociology. That was actually the reason that "Your House Will Pay" took me so much longer to write than my other books. I feel like it took me longer to get one of my main characters right, because I didn't have the confidence to just think I would get him right on the first go, so I put in a lot more work.

TU: I was surprised how much I related to Shawn.

CHA: Yeah, he's a character I relate to a lot and who I have a lot of respect for. I think he's a lot more likable than Grace is, but I also think that he has a borderline apathy too that is understandable.

TU: I was curious—with Grace's character—did you have any intentions in her name?

CHA: It was just so right there, honestly. She could have been a Eunice or an Esther, but those don't have the same English language connotation. But Grace would have been one of the few names I would have given her even if it didn't have that other meaning. But yeah, her name was intentional. It's such a prototypical second-generation Korean name.

TU: I wanted to talk about how relatable she is—some of the things she does are very cringe-worthy.

CHA: Yep, super cringey. I think that’s the right word for her.

TU: There’s the scene at the beginning at the memorial for a Black boy killed by the police where she has this conversion-like experience and suddenly gets what Black Lives Matter is about and feels this wave of emotion. Do you think that's a common experience for Korean millennials or people from that generation who are more sheltered?

CHA: Yeah, I think so. First of all, that was supposed to feel a little bit revival-y. She comes from this very churchy background. Grace is a reasonably decent person in that she does care about other people. She cares about people she doesn't know. And she cares passively about other people in a way that people who are not psychopaths do. But ultimately, she cares mostly about herself and her immediate family.

And I wanted to look at what happens when things really strike at home, when you don't have that option of getting distance—which is the position that Shawn and his family have been in this whole time. These things involve you directly, rather than as an idea, as something in the social atmosphere. Her experience of going to a rally and feeling moved, that's something that a lot of people feel. But then you go home.

TU: Reading this book in the context of the wave of BLM protests last summer—it felt like it was written for this time. Do you feel that at all?

CHA: I mean, 2020 was different—it did feel different from prior moments in this movement. But I started writing this book after Ferguson. And in that time period, between 2014 and 2020, we saw the rise and the establishment of the Black Lives Matter movement and we saw countless numbers of Black people who were murdered by police or by vigilante violence.

The part that might have been more timely is not the cycle of violence, it's the convergence of media attention and that feeling of reckoning that was put upon a lot of people who hadn't really done the work of confronting the racism in this country before. Grace would have been one of those people who was just posting the black square on Instagram and calling it activism. And that element of her social awareness and having to come to terms with the deeply personal, intimate nature of this violence is something that probably resonated more because of the events of last summer.

TU: There was the scene where Grace discovers the secret about her mother and goes to Shawn’s house—

CHA: Yeah, that's the ultimate cringe scene.

TU: If it had been written from her perspective, I think my soul might have left my body—but it was also relatable because in the process of the awakening that I've gone through—there are all these big wet, sloppy feelings sloshing around.

CHA: Yeah, that’s a good way to describe it.

TU: And you just want to spill all over the place. What do you do with those feelings?

CHA: I think her impulse to go to Shawn immediately was a pure one that also demanded a lot of him. I've seen this conversation a lot in the last year of people waking up and being like, “Oh, my God! There's racism!” And then Black people being like, “Yeah, we know.” And that's what I wanted to get across. She’s trying to get Shawn to help her with this body that they've been living with for 30 years. There’s that naïve, wide-eyed reaction of, “Oh, my God! What is going on in this country?”—when every single day of our history has been horrible.

Okay, so now you've figured this out, what do you do? I think the first impulse of a lot of people is to impose themselves on whatever Black people they know, whether it's to demand resources or to seek forgiveness. I didn't quite fit it into this book, but an impulse that a lot of people have is to go to somebody and say, “Tell me I'm one of the good ones.”

It's why you see white people prostrating themselves in front of Roxane Gay on Twitter every single day. And look, this is much better than the alternative, which is white people and non-Black people living in utter, happy ignorance. But there's a—you're right—a sloppiness. It puts a demand on people who are already marginalized for forgiveness and reassurance and validation that is really, really hard to watch.

TU: I was struck by the shame you felt about what happened to Latasha Harlins. I could relate to that shame even though I’m not Korean. And I wonder if you have any thoughts on the shame of having so much anti-Blackness within the Asian community. And it's not necessarily my family or even my community, but it still feels very bad.

CHA: I agree with you. Look, if I were a Korean person living in Korea, would I feel like anything anybody said about China had any bearing on me or my family? No, not at all. But here we are grouped together.

What does Wu Han Flu shit have to do with me?—I've never been to China, I don't have any Chinese heritage. But if people see me and think “China virus,” then that's suddenly my problem. So, part of it is very rational. If you're grouped with these people, then you are in the same boat. And some of it is obviously irrational too. There’s a tribal feeling that comes with, “This woman is like my mom or my aunt,” or “Oh, we went to the same market, probably.”

TU: I wonder if the type of collective shame that we feel is different from other minorities.

CHA: I think all minorities feel this in some sense. You know that feeling when there's a big crime committed, and you can feel everyone holding their breath, waiting to find out what the race of the perpetrator is? That's a tribal thing. I hope this person doesn't belong to my team. And I think white people have this less because they're not judged as part of a team, they're judged as individuals. But when you are part of a team—or when you're part of a group where if one person in your group does some shit, it's going to reflect back on your whole group—then of course you care about that.

TU: I wanted to talk about shame on an individual family level. With Grace and her mother, there was this family secret that crosses generations. For Grace, even though she wasn't there and she wasn't part of it, she is still dealing with this history and this trauma.

CHA: I don't have family issues like Grace does. But I was able to write her by intensifying the feelings that I have about my community and about smaller differences of opinion between me and my elders.

I wanted to write about a very good mother who's a very bad person. Because you do owe a huge duty to your mother—you owe a bigger duty to your mother than you do to a random stranger—you just do. And I wanted to look at where that duty becomes eclipsed by your duty to society. And I don't know the answer to that question. But I think that you do inherit the shames of your family, you don't really have a choice. Especially if the shame comes from your family having done great wrong to someone else, to someone else's family—those things don't go away.

I do think of Grace's story as one that is Korean American and particularly resonant with the experiences of second-generation kids. But she goes through a version of what every American has to go through, which is reckoning with the American heritage—whether that be that your family has been harmed, or your family did some harm, or your family has benefited from harm. And I think that's an important part of being American. You live in a country that is prosperous for some very specific reasons and that has done incredible amounts of harm over several centuries and looking at what that means for you. I think her story is a very American story in that way.

TU: I definitely agree. I see white people especially as being very resistant to that trajectory.

CHA: I agree. But I think every white person needs to own up to how much they've benefited from their grandparents being able to buy property when Black people were not allowed—even white people who don't have the benefits of intergenerational wealth often had the benefit of living in a white neighborhood with white public schools. What does that mean? It's all just a lot more personal than people pretend. People act like it's all about slavery. No, it's not all about slavery. It's about all the remnants of slavery that are very stubborn and legally encoded. Property ownership was legally discriminatory until the late 60s. That's our parents and grandparents.

TU: I wanted to talk about the ending of your book. When you started it, did you know what the ending would be?

CHA: Yep. Not in great detail. But I knew that I wanted to leave it open-ended. And I knew that I wanted to end with that scene in downtown LA, the beginnings of another riot or rebellion.

TU: This idea of destruction as a source of energy and hope for the future—in the context of everything that happened in 2020, that seems like such a resonant image.

CHA: When there were a few days of looting in LA, I made the argument—and I still stand by this—things don't get done when people are just quiet and take your promises and your IOUs.

The Rodney King uprising was horrible in a lot of ways. It resulted in 63 deaths, tons of property destruction and great mistrust between all the communities of Los Angeles. But it also changed the conversation in a way that would never have happened if there hadn't been that level of reaction. The LAPD—which is by no means a perfect police department, they have a lot of problems—but they used to be so much worse and they were forced to clean up their act.

The reason the George Floyd murder became such a big story was in part because of the extended reaction to it in the streets. Taking to the streets is an important way to exercise civilian power. And I do think that looting and destruction is a part of that. Do I believe that every looter is a revolutionary? No, obviously there's plenty of opportunism and general shit-headery. But it's all part of this broader organism we all belong to, and part of that movement does involve senseless destruction sometimes.

TU: One of the questions in the novel is “What is justice?” On the one hand, I was glad that Soon Ja Du’s character had the support of her church. But then that didn't feel like justice, either. Any happiness or future that she had felt wrong.

CHA: My character, Yvonne, she's a terrible person. She just is. She's a good mother; she's a terrible person. And Soon Ja Du—Oh, my God, just—horrible person. Has never shown an ounce of remorse. And that's part of why Yvonne doesn't show remorse. Sometimes I think if Soon Ja Du had served jail time, it would be a different story. But she got away with it.

I think it would have been better for her kids, except that they wouldn't have had their mom around. But it would have been better if she had dealt with it. There's less guilt on them.

TU: With the ending and the way that Shawn and Darryl [Shawn’s nephew] and Grace and Miriam come together—and the way that Shawn protects them in that moment and tells the crowd to go away—

CHA: But he's protecting his nephew. I didn't want Shawn to be this grand hero. Shawn gets in between this crowd and Grace and Miriam. But it's because he wants to protect Darryl. Grace sees that he has an effect on these people. And she sees him for a moment as this prophetic figure, larger than life. And then he coughs because it's smoky. And that's this very human moment. And she coughs because sometimes when you see someone else cough and then you notice it's smoky, you cough. There's a transfer of this physiological reaction. The city is catching on fire. And they both look to see what Miriam is pointing out. They click into the same wavelength for a couple paragraphs. So, the last couple hundred words of the book are in their joint POV. It's in a “they” POV, whereas the rest of the book has been in either Shawn’s or Grace’s point of view.

I decided that was hopeful enough. And I didn't think that it would be realistic or honest to make it any more hopeful. These two people who haven't really been seeing each other do see each other and realize that they share a part of this whole mess. That was the most optimistic thing that I could say. People have asked me, what happens after the book ends? And I don't know. And I think the answer is: Really nothing good. They're in a really bad, unworkable situation. People are dead. Someone's in jail who shouldn't be. The person who committed the crime, nobody wants them to go to jail either. No matter what happens, Darryl is deeply damaged. There's just not a good outcome. And I didn't think I could provide one. So I thought, we'll just end it here.

TU: I really liked the ending. Maybe I read more hope into it than was there.

CHA: I think the worldview is on the hopeful side. I'd say the way things are looking for the characters is not good.

TU: Do you think that through writing this book the shame that you felt was transformed in any way?

CHA: That feeling of shame—that feeling of responsibility—is not something that you can will away. You can't both benefit from history and be absolved. There's no absolution. You just have to own your piece. And so I will always—my feeling of shame affiliated with Soon Ja Du, that's a thing. My sense of what it means to be Asian American and the baggage that comes with that and our relationship to Blackness, those are all things that are not going away. And I will continue benefiting from them.

You can't have it both ways. It doesn't mean that anyone is born bad or damaged. I think people have this desire to have it all, to be the good white people or to be the good men. I think people want that. And you don't get to have it. And that doesn't mean you're horrible. But it does mean that you don't get to benefit in every way and still have everyone love you unconditionally. We all have our inheritance, we all have our baggage, and we have to deal with it.

TU: I think that's fascinating, because it sounds very cynical, but maybe it’s more so just a realism that the crime genre thrives on.

CHA: Yeah, there's no Kumbaya here. There are some situations you can't get out of. You can't undo the past. And you can't disown your part of it. You have to live your life in accordance with the existing infrastructure. You make your adjustments, try to be the best person you can. That's one of the things I wanted to explore with Grace and Miriam, that neither of them is perfect. And there is no perfect way to deal with the fact that your mom murdered a Black kid—you're either going to be a little bit disloyal as a daughter or a little bit racist, through no fault of your own. You're put in this compromised position. I don't have a solution to how to deal with being an American. But I have ideas.

Maylin Tu is a writer who grew up in Maine and Beijing. She is now based in Los Angeles where she writes about pop culture, religion, and identity.

Perfect discussion at the perfect time! 2020-2021 has shown that Anti-Blackness and Anti-Asian sentiments are real and dangerous. I’d always hoped that Asian Americans would understand and support the realities of Black Americans like myself as we are both minorities but it’s been a rocky path to where we are now. And I nearly gave up on white Americans because they kept dumping the responsibility and work of getting woke back on their Black friends. Steph Cha is so correct that there’s no absolution and no easy way out. We can’t keep sweeping the dirt of history under the rug. But this has given me hope and I definitely have to read this book!